...and here is the science!

The courses that I've done have independent research showing their efficacy. This information is found in full here:

https://mindfulnessinschools.org/research/published-research/

University of Exeter: Effectiveness of the Mindfulness in Schools Programme: non-randomised controlled feasibility study, August 2013

Although there is growing interest in mindfulness-based approaches for young people in schools 8,27 there are as yet few controlled trials, very few trials using a universal intervention and no trials of the MiSP curriculum. Results from this non-randomised controlled feasibility trial of the MiSP curriculum provide clear evidence of its acceptability, evidence of its impact on depressive symptoms and promising evidence of its efficacy in reducing stress and enhancing well-being.

The MiSP curriculum's primary aim is to teach young people skills to work with mental states, everyday life and stressors so as to cultivate well-being and promote mental health. One of the strengths of the study was the choice of a follow-up period in the most stressful part of the school year to test whether the MiSP curriculum conferred protection as evidenced through less self-reported stress and greater well-being. Moderate evidence for effects in the adjusted analyses suggests that the programme may confer resilience at times of greatest stress. Moreover, in line with other studies our findings suggest that young people who engaged more with the mindfulness practices also reported better outcomes (e.g. Biegel et al, 28 Huppert & Johnson 29 ).

This study provides preliminary evidence that the programme ameliorates low-grade depressive symptoms both immediately following the programme and at 3-month follow-up. This is a potentially very important finding given that low-grade depressive symptoms not only impair functioning but are also a powerful risk factor for depression in adolescents and adults. 4,30 Our findings are comparable with other mindfulness-based approaches with young people that also shown reductions in depressive symptoms (e.g. Biegel et al 28 ); however, this is the first study of a universal mindfulness-based intervention that appears to address a risk factor for depression and is consistent with a meta-analysis suggesting that preventing the onset of depression in adolescence is possible. 4

Although the effects of the MiSP curriculum on depressive symptoms in the intervention arm are significantly greater than those found in the control group, the change scores suggest these would prove to be small effects in a larger-scale randomised study (See Table 3 for the confidence intervals around the change scores). However, moving the population mean even a small amount on key variables that confer resilience, through a universal intervention, at a key developmental stage could potentially have more impact on mental health than interventions targeting young people either at risk for mental health problems or young people who have already developed mental health problems. 9 Indeed, a recent pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial (n = 5030) targeting young people at risk for depression compared a cognitive-behavioural intervention with an attention control intervention and usual school provision. 31 They found no benefit of the cognitive-behavioural arm over the other two arms; indeed, there was some suggestion of an exacerbation of depressive symptoms in the intervention arm that the authors attribute to increased awareness of problems.

Mindfulness-in-schools-pilot-study-2008

The specific benefits of mindfulness for cognitive function include improvements in focused and selected attention (e.g. Jha, Krompinger, & Baime, 2007; Tang et al., 2007),. Benefits for mental health including the reduction of symptoms of distress have been domenstrated in both clinical and non-clinical populations (e.g. Jha et al., 2007; Ma & Teasdale, 2004; Speca, Carlson, Goodey & Angen, 2000; Williams, Kolar, Reger, & Pearson, 2001). There is also

evidence of the enhancement of well-being including positive mood (Nyklíček & Kuijpers, 2008; Shapiro, Oman & Thoresen, 2008), self-esteem and optimism (Bowen et al., 2006) and selfcompassion and empathy (Shapiro, Schwartz, & Bonner, 1998; Shapiro, Astin, Bishop & Cordova, 2005; Shapiro, Brown, & Biegel, 2007). Mindfulness-based interventions have also shown substantial benefits for physical health, including the management of chronic pain (e.g.

Grossman, Tiefenthaler-Gilmer, Raysz, & Kesper, 2007; Morone, Greco, & Weiner, 2008), improved neuroendocrine and immune functioning (Davidson et al., 2003; Tang et al., 2007) and improvements in health-related behaviours such as reductions in binge eating (Kristeller & Hallett, 1999) and substance misuse (Bowen et al., 2006).

Far less research has been undertaken with children or adolescents, but in light of the cognitive, emotional and social benefits of mindfulness meditation in adults, its application within the school context is becoming more widespread (see for example the report by the Garrison Institute, 2005). However in the published literature to date there has been little systematic evaluation of the effects of mindfulness training in children. A recent review by Burke (2009)

summarises the limited evidence published to date regarding children and adolescents. We focus here on the latter group, in whom mood is known to be volatile, and where there is evidence of low levels of satisfaction with school compared to younger children (nef, 2004).

The main finding of this study was a significant improvement on measures of mindfulness and psychological well-being related to the degree of individual practice undertaken outside the classroom. Previous studies in adults have also shown that positive benefits are associated with a greater amount of practice (eg Carmody and Baer 2008; Carson et al, 2004). Carmody and Baer reported that time spent engaging in home practice of formal meditation exercises was

significantly related to extent of improvement in most facets of mindfulness and several measures of symptoms of psychological well-being. Furthermore, in the present study, the impact of practice on psychological well-being and mindfulness was significant after allowing for the influence of personality. It should be noted that the significant impact of amount of practice on mindfulness and well-being occurred in the context of a marginally significant multivariate

model. We chose to interpret this result as meaningful given the exploratory nature of the study. The lack of a significant overall group difference between the intervention and control classes may reflect the small amount of exposure to MBSR that was provided in the study. Adults typically receive eight 2-hour sessions of training and are encouraged to do around 40 minutes per day of individual practice. In contrast, the adolescents in this study received only

four 40-minute sessions and were encouraged to do 8 minutes per day of individual practice. In fact, daily practice was rare and only one-third of the group practised three times a week or more, while another third practised once a week or less. Our finding that amount of practice

was significantly related to improvements on two of the three outcome measures (mindfulness and well-being), despite students having had less than 3 hours of mindfulness training (compared with typically 16 hours for adults), suggests that this is a very promising intervention for adolescents. The effects may well be stronger if training time is increased. It is noteworthy that 43% of the students reported that they would have liked the training course to be longer

(Table 4).

It may be surprising that scores on the mindfulness scale did not show a significant benefit in the intervention compared to the control condition, since training in mindfulness would be expected to improve scores on a mindfulness scale. However, it is possible that when a person first begins learning about mindfulness, one of the key early realisations is that they are not very mindful in their daily life. Hence, their ratings of their levels of mindfulness may show aninitial decrease, until training is sufficient to lead to an improvement in day-to-day mindfulness

skills. Whether or not this is an explanation for the lack of a main effect of mindfulness training on scores in the mindfulness scale, it is consistent with our finding of a significant improvement in mindfulness scores in relation to the degree of practice.The questionnaire measures used in this study have all been developed and validated for adult samples, although in some cases the validation includes participants as young as 17 (eg WEMWBS, Tennant et al 2007). However, the data from the baseline phase indicate that in terms of their distributional properties,

these measures appear to perform well in this adolescent sample.

We further explored the baseline data by combining the baseline scores of the two groups, since there were no significant differences between them. This revealed some interesting associations between the psychological measures and personality variables, using the Big Five model of personality (McCrae & Costa, 1987). High levels of conscientiousness and emotional stability were associated with high baseline scores on all three psychological measures - mindfulness, resilience and well-being. In addition, high scores on extraversion and openness to experience were associated with high scores on resilience and well-being. High scores on agreeableness were associated only with resilience.

Cardif University, Mindfulness in Schools A mixed methods investigation of how secondary school pupils perceive the impact of studying mindfulness in school and the barriers to its successful implementation

....Consistent with prior theoretical assumptions (Baer, 2003), participants in all three focus groups and all eight interviewees reported increased control over their cognitive processing of information as a result of learning mindfulness-based practices. In particular, a number of interviewees reported experiencing less rumination and excessive worry over issues such as upcoming exams and tests that

would previously have impacted on their functioning and prevented them from sleeping.

...Thematic analysis of both interview and focus group data revealed that a number of participants considered that the application of mindfulness-based practices enabled them to control emotions such as frustration and anger in a more positive way. This

perspective was particular prevalent in pupils’ discussions relating to how they dealt with interpersonal disputes. These findings offer tentative support for prior claims that mindfulness training can positively influence the way individuals respond to negative emotions (Farb et al., 2010). However, this perception was not so prevalent within questionnaire data, which found that the majority of pupils perceived mindfulnessbased

practices to be either ‘Slightly’ or ‘Moderately’ helpful for dealing with their emotions.

...Further analysis of the qualitative data also revealed that a number of pupils perceived that their use of mindfulness techniques had help them to regulate their behaviour more positively, particularly during interpersonal disputes. For these individuals such changes were attributed in part to an enhanced perception of their own mental states.

...A further perceived impact of studying mindfulness noted by pupils was that of improved interpersonal relationships. A number of pupils, particularly from school B (state educated), described how their application of mindfulness techniques had helped to calm them down during disputes with family members and to enable them to be more empathetic and considerate towards the other person(s) involved.

However, a lack of consensus was found concerning participants’ perspective on this point and a number of pupils (n=14, 30.4%) reported that the mindfulness techniques they had learnt had no impact at all on their interpersonal relationships. Such findings suggest distinct variability in how influential mindfulness practices may be in promoting pupils social and emotional competence and interpersonal skills. Analysis

of questionnaire data found that the perceptions of pupils from school B in relation to such impact were found to be statistically more favourable than those reported from pupils’ from school A (Privately educated). In addition, ratings were also higher from pupils completing the ‘. b’ course in the Spring term rather than Summer term.

https://mindfulnessinschools.org/research/published-research/

University of Exeter: Effectiveness of the Mindfulness in Schools Programme: non-randomised controlled feasibility study, August 2013

Although there is growing interest in mindfulness-based approaches for young people in schools 8,27 there are as yet few controlled trials, very few trials using a universal intervention and no trials of the MiSP curriculum. Results from this non-randomised controlled feasibility trial of the MiSP curriculum provide clear evidence of its acceptability, evidence of its impact on depressive symptoms and promising evidence of its efficacy in reducing stress and enhancing well-being.

The MiSP curriculum's primary aim is to teach young people skills to work with mental states, everyday life and stressors so as to cultivate well-being and promote mental health. One of the strengths of the study was the choice of a follow-up period in the most stressful part of the school year to test whether the MiSP curriculum conferred protection as evidenced through less self-reported stress and greater well-being. Moderate evidence for effects in the adjusted analyses suggests that the programme may confer resilience at times of greatest stress. Moreover, in line with other studies our findings suggest that young people who engaged more with the mindfulness practices also reported better outcomes (e.g. Biegel et al, 28 Huppert & Johnson 29 ).

This study provides preliminary evidence that the programme ameliorates low-grade depressive symptoms both immediately following the programme and at 3-month follow-up. This is a potentially very important finding given that low-grade depressive symptoms not only impair functioning but are also a powerful risk factor for depression in adolescents and adults. 4,30 Our findings are comparable with other mindfulness-based approaches with young people that also shown reductions in depressive symptoms (e.g. Biegel et al 28 ); however, this is the first study of a universal mindfulness-based intervention that appears to address a risk factor for depression and is consistent with a meta-analysis suggesting that preventing the onset of depression in adolescence is possible. 4

Although the effects of the MiSP curriculum on depressive symptoms in the intervention arm are significantly greater than those found in the control group, the change scores suggest these would prove to be small effects in a larger-scale randomised study (See Table 3 for the confidence intervals around the change scores). However, moving the population mean even a small amount on key variables that confer resilience, through a universal intervention, at a key developmental stage could potentially have more impact on mental health than interventions targeting young people either at risk for mental health problems or young people who have already developed mental health problems. 9 Indeed, a recent pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial (n = 5030) targeting young people at risk for depression compared a cognitive-behavioural intervention with an attention control intervention and usual school provision. 31 They found no benefit of the cognitive-behavioural arm over the other two arms; indeed, there was some suggestion of an exacerbation of depressive symptoms in the intervention arm that the authors attribute to increased awareness of problems.

Mindfulness-in-schools-pilot-study-2008

The specific benefits of mindfulness for cognitive function include improvements in focused and selected attention (e.g. Jha, Krompinger, & Baime, 2007; Tang et al., 2007),. Benefits for mental health including the reduction of symptoms of distress have been domenstrated in both clinical and non-clinical populations (e.g. Jha et al., 2007; Ma & Teasdale, 2004; Speca, Carlson, Goodey & Angen, 2000; Williams, Kolar, Reger, & Pearson, 2001). There is also

evidence of the enhancement of well-being including positive mood (Nyklíček & Kuijpers, 2008; Shapiro, Oman & Thoresen, 2008), self-esteem and optimism (Bowen et al., 2006) and selfcompassion and empathy (Shapiro, Schwartz, & Bonner, 1998; Shapiro, Astin, Bishop & Cordova, 2005; Shapiro, Brown, & Biegel, 2007). Mindfulness-based interventions have also shown substantial benefits for physical health, including the management of chronic pain (e.g.

Grossman, Tiefenthaler-Gilmer, Raysz, & Kesper, 2007; Morone, Greco, & Weiner, 2008), improved neuroendocrine and immune functioning (Davidson et al., 2003; Tang et al., 2007) and improvements in health-related behaviours such as reductions in binge eating (Kristeller & Hallett, 1999) and substance misuse (Bowen et al., 2006).

Far less research has been undertaken with children or adolescents, but in light of the cognitive, emotional and social benefits of mindfulness meditation in adults, its application within the school context is becoming more widespread (see for example the report by the Garrison Institute, 2005). However in the published literature to date there has been little systematic evaluation of the effects of mindfulness training in children. A recent review by Burke (2009)

summarises the limited evidence published to date regarding children and adolescents. We focus here on the latter group, in whom mood is known to be volatile, and where there is evidence of low levels of satisfaction with school compared to younger children (nef, 2004).

The main finding of this study was a significant improvement on measures of mindfulness and psychological well-being related to the degree of individual practice undertaken outside the classroom. Previous studies in adults have also shown that positive benefits are associated with a greater amount of practice (eg Carmody and Baer 2008; Carson et al, 2004). Carmody and Baer reported that time spent engaging in home practice of formal meditation exercises was

significantly related to extent of improvement in most facets of mindfulness and several measures of symptoms of psychological well-being. Furthermore, in the present study, the impact of practice on psychological well-being and mindfulness was significant after allowing for the influence of personality. It should be noted that the significant impact of amount of practice on mindfulness and well-being occurred in the context of a marginally significant multivariate

model. We chose to interpret this result as meaningful given the exploratory nature of the study. The lack of a significant overall group difference between the intervention and control classes may reflect the small amount of exposure to MBSR that was provided in the study. Adults typically receive eight 2-hour sessions of training and are encouraged to do around 40 minutes per day of individual practice. In contrast, the adolescents in this study received only

four 40-minute sessions and were encouraged to do 8 minutes per day of individual practice. In fact, daily practice was rare and only one-third of the group practised three times a week or more, while another third practised once a week or less. Our finding that amount of practice

was significantly related to improvements on two of the three outcome measures (mindfulness and well-being), despite students having had less than 3 hours of mindfulness training (compared with typically 16 hours for adults), suggests that this is a very promising intervention for adolescents. The effects may well be stronger if training time is increased. It is noteworthy that 43% of the students reported that they would have liked the training course to be longer

(Table 4).

It may be surprising that scores on the mindfulness scale did not show a significant benefit in the intervention compared to the control condition, since training in mindfulness would be expected to improve scores on a mindfulness scale. However, it is possible that when a person first begins learning about mindfulness, one of the key early realisations is that they are not very mindful in their daily life. Hence, their ratings of their levels of mindfulness may show aninitial decrease, until training is sufficient to lead to an improvement in day-to-day mindfulness

skills. Whether or not this is an explanation for the lack of a main effect of mindfulness training on scores in the mindfulness scale, it is consistent with our finding of a significant improvement in mindfulness scores in relation to the degree of practice.The questionnaire measures used in this study have all been developed and validated for adult samples, although in some cases the validation includes participants as young as 17 (eg WEMWBS, Tennant et al 2007). However, the data from the baseline phase indicate that in terms of their distributional properties,

these measures appear to perform well in this adolescent sample.

We further explored the baseline data by combining the baseline scores of the two groups, since there were no significant differences between them. This revealed some interesting associations between the psychological measures and personality variables, using the Big Five model of personality (McCrae & Costa, 1987). High levels of conscientiousness and emotional stability were associated with high baseline scores on all three psychological measures - mindfulness, resilience and well-being. In addition, high scores on extraversion and openness to experience were associated with high scores on resilience and well-being. High scores on agreeableness were associated only with resilience.

Cardif University, Mindfulness in Schools A mixed methods investigation of how secondary school pupils perceive the impact of studying mindfulness in school and the barriers to its successful implementation

....Consistent with prior theoretical assumptions (Baer, 2003), participants in all three focus groups and all eight interviewees reported increased control over their cognitive processing of information as a result of learning mindfulness-based practices. In particular, a number of interviewees reported experiencing less rumination and excessive worry over issues such as upcoming exams and tests that

would previously have impacted on their functioning and prevented them from sleeping.

...Thematic analysis of both interview and focus group data revealed that a number of participants considered that the application of mindfulness-based practices enabled them to control emotions such as frustration and anger in a more positive way. This

perspective was particular prevalent in pupils’ discussions relating to how they dealt with interpersonal disputes. These findings offer tentative support for prior claims that mindfulness training can positively influence the way individuals respond to negative emotions (Farb et al., 2010). However, this perception was not so prevalent within questionnaire data, which found that the majority of pupils perceived mindfulnessbased

practices to be either ‘Slightly’ or ‘Moderately’ helpful for dealing with their emotions.

...Further analysis of the qualitative data also revealed that a number of pupils perceived that their use of mindfulness techniques had help them to regulate their behaviour more positively, particularly during interpersonal disputes. For these individuals such changes were attributed in part to an enhanced perception of their own mental states.

...A further perceived impact of studying mindfulness noted by pupils was that of improved interpersonal relationships. A number of pupils, particularly from school B (state educated), described how their application of mindfulness techniques had helped to calm them down during disputes with family members and to enable them to be more empathetic and considerate towards the other person(s) involved.

However, a lack of consensus was found concerning participants’ perspective on this point and a number of pupils (n=14, 30.4%) reported that the mindfulness techniques they had learnt had no impact at all on their interpersonal relationships. Such findings suggest distinct variability in how influential mindfulness practices may be in promoting pupils social and emotional competence and interpersonal skills. Analysis

of questionnaire data found that the perceptions of pupils from school B in relation to such impact were found to be statistically more favourable than those reported from pupils’ from school A (Privately educated). In addition, ratings were also higher from pupils completing the ‘. b’ course in the Spring term rather than Summer term.

The two course options, in detail

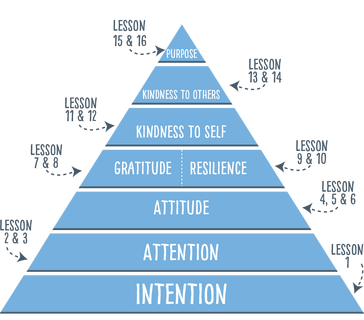

YOUTH MINDFULNESS - AGES 6-111. Training the mind - INTENTION

- what is the mind? - Nero plasticity - Basic brain science - patterns and computer games - how has your brain grown? Drawing - riddle what time is it? Now - meaning of mindfulness - breathing in and out practice - potential benefits of mindfulness - connection - Sharing a personal story - flow and music - Key principles of A. you have to choose the train, B. Get in the zone, C. Respect, D. Enjoy yourself - individual reasons discussed 2. Attention - re-cap - What is attention - The wheel of mindfulness - sounds - counting - Challenge – can you keep your mind in one place? - 'up' and discussion about spotting the squirrel - what did you learn? 3. The benefits of breathing - slap, clap, snap, snap. - breathing and standing practice - why focus on breathing? Interconnectedness - analogy of weather/tree - breathing practice - paired group discussion - spot the squirrel practice - how have you improved? - where's Wally? 4. Notice and allow - spot the squirrel discussion: where did your mines go last week? - being a leader - standing practice – seaweed and a stormy sea - sitting breathing practice - what emotions happen? - Pushing hands - mindful attitude - Master oogway video - quotes from kids - acknowledging and saying hello to what's happening in our minds - glitter bottle - sitting practice with posture 5. Beginner's mind - movement meditation - body scan - discussion on mindful attitude - box of mystery: next moment is unknown - Maltese are meditation - beginner's mind - Jonathan reclaiming hearing - listening practice 6. Willpower Willpower lecture Fast and slow meditation on movement Breathing practice Discussion time – difficulty and helpful? Game – the watcher and thoughts, feelings, impulses, sensations, it sounds. Notice and allow Willpower challenge. Longer practice 7. Being grateful Thinking versus sentencing Movement and tackling practice Setting practice Stabilising attention Being grateful like Nick Three good things practice Cultivating gratitude – lying down practice 8. Appreciating others Self massage Body scan Enquiry Moving art Mindfulness and gratitude 20 good things Gratitude letter Sitting practice Pair discussion 9. Learning Resilience Breathing mindfull, at the base of the tree Mindful musical statutes Mindsight Reaction vs Response Ice in the hand! Who’s in control? Mindful mountain 10. Mindsight - learning friendly self awareness Mindful Movement Sitting - thoughts lead to feelings Stories Thoughts are not facts! River of thoughts Mindsight - Master Oogway (Kung Fu Panda) Sounds, thoughts, emotions 11. Building our kindness- all humans want happiness Movement meditation Animal mind Why did you come to school today? Happiness Acts of kindness Growing happiness Sending kindness 12. Being a good friend Mindful walking Pushing, pulling, ignoring What makes a good friend? Sending more kindness 13. Be an everyday hero Mindfulness to kindfulness Mystery buddy Heros What would you do? Seed of kindness Sending Kindness 14. Kind Action Mindful musical statues Why is kindness important to grow? Ripples of kind acts Kindness and happiness go together Experiment Sending kindness 15. Looking back Seaweed meditation Deep ocean mind The whole course in 5 minutes Stopping and breathing What’s most valuable to you? Mindfulness to kindfulness 16. Looking forward Who do you admire? Newspaper article of the future Aspiration statement Drawing each other Sing a song of celebration Recognising potential |

MINDFULNESS IN SCHOOLS PROJECT - AGES 10-17Introduction –

- Brain training neuroplastic - where is the mind? - kung fu panda present moment - mini meditation - managing difficult emotions - possibilities - other students - practice 1. Playing attention - Spotlight - body scan - puppy mind - finger breathing 2. Taming the animal mind - mind is an animal - Attenborough attention Vs fighting - FOFBOC - anchoring remind in the body 3. Recognising worry - 7–11 practice breathing - thinking and sensing mind - story and anticipation - Hot cross bun affect - rumination in action - Bad itation 4. Being here now reacting to responding - autopilot - Savouring food - Liking versus disliking - impulses and reactions - FOFBOC 5. Mindful movement - practice - flow - zone sports - The last samurai - balance of sensing and thinking - walking practice - Learning to slow down 7. Stepping back from thoughts - traffic in the mind right now? - headspace - stepping back and brain science - thought. Buses - diary of thoughts that pull you on board 8. Befriending the difficult - shit happens – react or respond - stress and situations - physiology of stress - fight flight freeze - draw your stress signature - Electric shock ball game - allow the feelings and breathe with them - Camp fire time - The guest house by rumi 9. Taking in the good - heart centred - grapefulness - holocaust survivor - positive thinking attitude - attitude of gratitude - fofboc - video of people expressing gratitude - three good things practice 10. Pulling it together - quiz - sunscreen song advice - writing a letter to self - fill in a questionnaire |

Proudly powered by Weebly